Photo by Tak, Flickr.

Twenty-three experts involved in the study “Antarctica and the strategic plan for biodiversity,” recently published in PLoS Biology, debunked the popular view that Antarctica and the Southern Ocean are in a better environmental shape than the rest of the world. In fact, the difference between the status of biodiversity in the region and planet Earth as a whole is negligible.

Coming from a wide array of disciplines such as Law, Zoology, International Affairs, and Marine Biology, the researchers reached their conclusion after evaluating empirical evidence and expert knowledge against the Aichi targets in the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity. The CBD provides the basis for taking effective action to curb biodiversity loss across the planet by 2020.

“People tend to think that Antarctica and the Southern Ocean are healthier ecosystems because they are remote and would (or should) have been less exposed to human impact,” said Deng Palomares, who participated in the study as the Sea Around Us expert on catches in the Antarctic region. Due to that common belief, the Aichi targets have never been applied to those areas which, together, account for about 10 per cent of the globe’s surface.

The absence of appropriate quantitative trend indicator data on biodiversity state, pressures, drivers, and response for the region is dangerous because researchers, governments, and the general public may never know how much biodiversity there was before and, consequently, how much has disappeared.

But, what’s spoiling this ought-to-be-pristine environment in the first place? “Certain rich countries have the means and resources to send vessels there under the guise of ‘research’ and are contributing to prospecting. The Antarctic offers deep-sea fisheries an almost unregulated fishing due to its remoteness from administrative countries and international bodies or authorities,” Palomares explained.

Legal fisheries in the area, however, are managed under an ecosystem-based approach. This has been beneficial until now, but researchers don’t think it is sustainable in the long run. “First of all, the habitat is subjected to changes in temperature and thus to climate change. Second, the species living in these ecosystems are mostly deep-water, long-lived species and, thus, highly vulnerable to environmental and exogenous impacts. At the rate of the extraction happening now, on a comparatively low surface area, none of these extracted species will survive to 2020. There will be extinctions of a level of the sea that usually should be immune to exogenous factors. The efficiency of fishing is so high that such fishing is not sustainable anymore,” Palomares said.

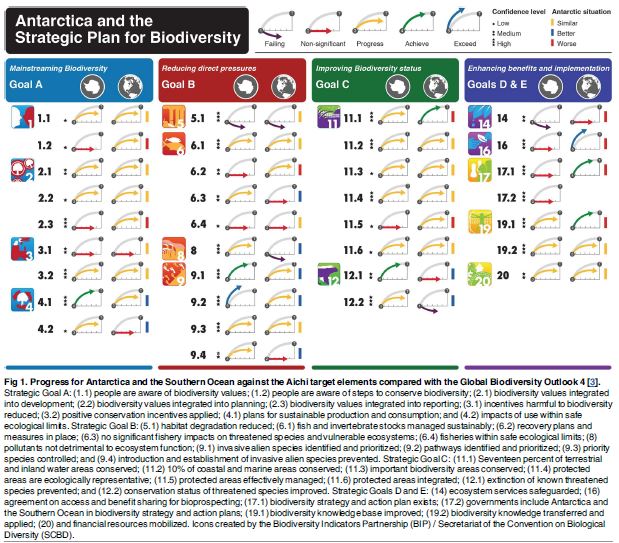

Guided by structured worksheets, the authors of the PLoS-B study met in small groups and completed three tasks: (1) identify the relevance of each of the 20 Aichi targets to the Antarctic; (2) consider the evidence available to assess the current status of each target for the region; and (3) use this evidence to assess the extent to which the Aichi targets are likely to be realized for the Antarctic region by 2020.

For the third task, participants were also asked to assign one of five possible trajectories to each

target. The full group then made a final allocation of one of the five trajectories for each Aichi target. Each decision was assigned a level of confidence (low, medium, or high) based on available evidence and following the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change guidelines on uncertainty.

Following their findings around the biodiversity and conservation management outlook for Antarctica and the Southern Ocean being no different to that for the rest of the world, the experts came up with some solutions to slow down and eventually halt biodiversity losses in Antarctica.

According to the Sea Around Us’ Senior Scientist, countries, particularly those who claim certain pieces of the Antarctic, should accept to include the Southern Ocean in global scale management. “That is, to include the Antarctic in any plan of action to protect biodiversity loss, notably via the United Nations or any regional body that will have policy impacts on governments involved in any activity in the region, with an emphasis in the extraction of biodiversity for commercial and research purposes.”

If, in an ideal world, those objectives were accomplished, would that be enough to protect the Southern Ocean? “No, because whatever happens elsewhere will affect the Antarctic. The oceans are connected and anything we do in one part of the world will affect the other. Antarctica will suffer the most because it is the most vulnerable. That is why, in the end, global action is needed,” Palomares said.

Deng Palomares is a Senior Scientist with the Sea Around Us project at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. To schedule interviews with her, please contact Valentina Ruiz Leotaud v.ruizleotaud@oceans.ubc.ca | 604.8273164